I’ve recently returned from a trip to Ireland. It was my first time there; I went to escape the heat of southern France. What I found—with the help of some wonderful people—is a place that is bigger than words can convey. Magic and energy and connection. Inescapable history, remembered pain. Ireland is a place of striking contrasts. There is wild surf crashing against rough rocks and impossible cliffs, while woolly sheep quietly graze nearby on velvety green grass. There is the historical pain of attempted colonization, while the people are also the friendliest I’ve ever encountered. There is divine music and Guinness on tap. It’s a little slice of heaven right here on earth.

It was a long trip—which means lots of photos to show and stories to tell—so I’m dividing this into two posts. I spent a little over two weeks in County Donegal, and a few days on either end in other places. This first post covers the “other places.”

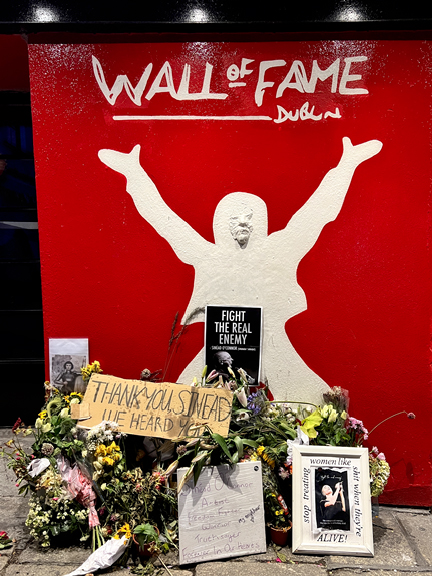

First stop, Dublin

Dublin formed the bookends of my trip because of its airport. A late arrival on the Emerald Isle gave me an overnight stay, so I had the opportunity to visit Trinity College and its splendid old library.

After that, I found a quick lunch and headed to the station to catch my train for Westport, where I’d spend the next several days.

Last stop, Newgrange

A few weeks later, at the end of my Irish stay, I visited the Neolithic site at Brú na Boínne before returning to Dublin for my flight. This is one tightly-controlled place to visit: it’s nearly mandatory to book ahead; once you have a ticket, there is no variation in entry times (I was over an hour early, and couldn’t get in until my appointed time); and they keep everyone moving at a fairly quick pace that makes photography a little tricky. That said, it’s quite an impressive place to see.

Four days in Westport

After Dublin, I enjoyed four wonderful days in the area around Westport, a town that’s located on Clew Bay along the rugged west coast. I was hosted by my multi-talented friend Connie, a musician who sometimes guides curious visitors around County Mayo.

My first evening in Westport is memorable because I think of it as my real welcome to Ireland and the glory that is traditional Irish music played in a room full of happy people. The place was already packed when we arrived; Connie made his way to the musicians’ corner, and I felt lucky to find a seat at the back of the room. As the evening progressed, I was able to sit closer to the musicians, as you can see in the photos below.

I had arrived in Ireland with a list of things to see and do, and this experience was near the top of that list. I can’t imagine a better place to start than Matt Molloy’s, and as the days and weeks of my journey rolled by, I quaffed quite a few pints of Guinness in several more fine bars, tapping my feet to the music.

Westport, Day 1

The day dawned dove grey, and Connie drove us southeast to the Ross Errilly Friary, built around 1460. As with much of Ireland, there was an ebb and flow pattern to the tolerance shown by occupying English forces toward the Catholic clergy, although the low point here seems to have been when the friary was attacked by Cromwell’s forces in 1656. The monks had fled, but the building and its grounds were badly damaged. The monks returned again and again, until finally the community was closed in 1832.

Westport, Day 2

The next day, Connie turned the car toward the beautiful Doolough Valley. I heard several people say that it never looks the same from one day to the next, which is easy to imagine. The weather that day helped—some wind and ominous clouds—and I could sense sadness, grief and desolation here, even before I heard the story that Connie told me that day.

Living skeletons

On March 30, 1849, 600 poor, starving people left their homes to walk 19 kilometers through freezing rain and heavy winds. Most did not survive.

It was the time of the Great Famine, but “famine” is a tricky word; what was happening in Ireland was nothing short of ethnic cleansing. There was plenty of food. The British Empire was at its peak of wealth and power, and had the ability to care for and feed its citizens. But most of the food was exported, and the Irish were left with rotten potatoes.

One dreadful event took place in Doolough Valley. The people of Louisburgh were awaiting an inspection, a humiliating process in which they had to pass a review by the local authorities to prove that they were poor enough to receive either food relief or a work permit. The authorities never held the inspection, instead moving south to the Delphi Lodge. The people were told to show up at the lodge at 7:00 the next morning, or they would receive no help.

With little choice, they walked. Men, women, and children, physically weak and wearing insufficient clothing, walked through difficult wintry weather to arrive at the lodge in time. Many had no shoes. Some died along the way. The survivors appeared at the door of the lodge, but were turned away because the inspectors were enjoying their lunch. The people were denied relief of any kind and told to leave. Most died on the return walk; many bodies were left at the side of the road for days.

It’s a story that is similar to many others in Ireland during this time, but there’s a special twist at the end.

It turns out that the Choctaw Nation of the United States, having 20 years earlier survived their own death march on the Trail of Tears, somehow heard of the travails of the Irish people. The Choctaw, along with four other tribes, were forcibly evicted from their lands in the southeastern U.S., and marched to unknown lands in Oklahoma. Many died along the way, and the survivors saw their way of life disappear.

And yet, when they learned of the starvation in Ireland, they managed to pool together $170, around $5,000 in today’s money, to send to Ireland. Many of these people were themselves poor, hungry and ill, unlikely candidates to provide aid to unknown people across an ocean. The Irish people have never forgotten, and there remains a strong bond between these two nations.

In County Cork, there is a lovely monument to the Choctaw which I’d like to see one day. And here in Doolough, there is a grateful mention of the Choctaw. A memorial was erected in 1994, to honor the memory of those people who suffered and died on that horrible walk through the Doolough Valley. The occasion was a 1991 memorial walk, from Louisburgh to the Delphi Lodge. Desmond Tutu walked here that day. And so did members of the Choctaw Nation.

“Nothing divides the Choctaw people from the Irish except for the ocean…. In 2020 the death toll (from Covid-19) was particularly acute in the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Reservation. The Irish, stating that they were “paying it forward” with their aid from the Choctaws in mind, took up a very sizeable donation with which to aid and assist the Navajo and Hopi.” 1

1 Choctaw Nation, http://www.choctawnation.com

Other references:

– Ireland Calling, ireland-calling.com

– Irish Central, irishcentral.com

– Irish American Journal, irishamericanjournal.com

– Smithsonian Magazine, smithsonianmag.com

– Atlas Obscura, atlasobscura.com

Westport, Day 3

Our destination this grey morning was Achill Island, but first Connie had a little surprise in store for me. We stopped at a church in Newport, and when I walked inside, I’m pretty sure that I gasped when I saw the stunningly beautiful stained glass windows behind the altar. With that one window, I turned into a big fan of Harry Clarke, a fascinating Irish artist who lived from 1889 to 1931.

After that brief stop, we turned toward Achill Island. As we crossed the bridge to the island, we were welcomed by rain and wind, both growing steadily in intensity.

Our first stop was to visit a cemetery and castle that had been held by Grace O’Malley—Gráinne Ni Mháille in Irish—who is often called the Pirate Queen.

Grace O’Malley, the pirate queen

Grace O’Malley had given birth hours earlier, and was nursing her son Tibbett, when Algerian pirates attacked and boarded her ship. Carrying her swaddled son, she grabbed two guns and stormed up to the deck, where she shot the invading officers and captured the other ship.

I want to know this woman. I want our daughters to be just as fierce as Grace O’Malley, who was born in 1503, into the County Mayo shipping clan of Uí Mháille. The clan was based around Clew Bay, which is studded with tiny islands that allow ships to hide. She took an interest in the sea from the beginning; at the age of 12, she cut off her hair and demanded that her father take her with him on a merchant voyage. Her Gaelic name was Gráinne Ni Mháille, often condensed to Granuaile.

Granuaile was married at the age of 15 to the son of a neighboring clan. Three children and 14 years later, he died, and she took over his ships. When her own father died, she became the leader of her clan—but as a woman, she could not be called chieftain—gaining more ships and more men, and the respect of all.

She was dubbed “The Pirate Queen” by the English, but in reality, Granuaile was probably not so much a pirate as an especially skilled mariner who broke the mold of what society thought women should be. She ran an international shipping empire; she charged fees to other merchants who wished to do trade at her ports, as well as fees for safe passage. She was a passionate defender of her family and her culture. For most of her life, she commanded at least 200 men and several ships, and had the respect of Irish and English alike.

Sir Henry Sidney, Lord Deputy of Ireland, who met Granuaile in 1577 wrote: “A most famous, feminine sea captain… famous for her stoutness of courage… commanding three galleys and 200 fighting men… This was a most notorious woman in all the coasts of Ireland.”1

During the Tudor reign, the English ramped up their efforts to subdue the Irish chieftains and take over their lands. Sir Richard Bingham was appointed governor of Connaught, and caused Granuaile many years of great hardship. He wrote of her that she “had overstepped the part of womanhood.”2

In 1593, when Bingham captured and imprisoned Granuaile’s son Tibbett, she had had enough. At the age of 63, she sailed all the way from the west coast of Ireland and up the Thames River to demand an audience with Queen Elizabeth I. The voyage was courageous enough, but in order to see the queen she had to draw on every bit of her shrewd political abilities to navigate the tricky path that was set out for her. She prevailed, and these two formidable women met as equals for a conversation; Granuaile did not curtsy to the queen, and apparently Elizabeth was fascinated by her Irish counterpart. Granuaile was granted her son’s freedom, the return of her properties, and the ability to maintain her life on the sea, in return for promising that her ships would defend the crown.

Granuaile died at the age of 73 in 1603, the same year as Queen Elizabeth I.

Biographer Anne Chambers wrote: “Enduring danger and hardship by land and especially by sea, O’Malley’s maritime skill gave her role as leader a double edge. It took immense skill and courage to ply the dangerous Atlantic Ocean and to withstand the physical hardships of life at sea. It is her leadership at sea that sets Grace O’Malley apart from every other documented female leader in history.”3

1, 3 : History Extra, http://www.historyextra.com

2 : Royal Museums Greenwich, http://www.rmg.co.uk

Reference: National Geographic, http://www.nationalgeographic.com

I’m not done yet

Connie and I drove around the region for three days, and only barely scratched the surface of what is there, quietly waiting to be discovered. My brief visit was like taking the red bus tour of London, a teaser for future journeys.

This is a land that reveals itself through slow seeing, the kind you can only do by walking for miles, or better yet, by sitting still.

I want to hike the hills of lovely Connemara, and climb the pilgrim’s path up Croagh Patrick. I want to sit by the cliffs of Achill Island during a wild storm and watch the sea furiously hurl its worst against the rocks. I want to walk in the footsteps of Granuaile and visit her castle on Clare Island. I want to nurse more pints of Guinness, listening to the music of Ireland and surrounded by friends I’ve yet to meet. Hmm… this could all take a while.

A very timely posting as I will be heading to Westport tomorrow to explore the area. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Hello Peter, thank you for writing. I hope you have a splendid time in Westport. Slainté!

LikeLike

Isn’t it satisfying to have a long-desired destination crossed off your bucket list? Such a wonderful description of your time there. You take the most interesting pictures, too.

LikeLike

Hello Cathy,

How nice to hear from you! It is definitely satisfying to have enjoyed a good trip, but I can’t really say that it’s now crossed off my list. I really liked Ireland, and I’m sure I’ll go back at least once more. Thanks so much for you lovely compliment, and I’m tickled that you enjoy my choice of photos!

Thanks for writing, and slanté,

Lynne

LikeLike

I’ve never considered not taking something off my bucket list because I’ve done it or gone there. What an interesting idea I’ll be giving more thought to.

LikeLike

Yes, it becomes a puzzle: to return to a place I really liked, or to set off for lands I’ve yet to see? So many interesting things, so little time.

LikeLike

Beautiful, beautiful pictures and fascinating stories. We went to Ireland for three weeks in 2019 and just loved it. I look forward to the second post!

LikeLike

Hello Duncan,

Thank you for writing, and for your nice compliments. I can so easily picture you in Ireland, surrounded by all that magic.

LikeLike

Delightful on many, many levels. Makes me want to visit Ireland again…since I too feel I just barely scratched the surface. I love how you find your way through a region. So many things I didn’t even know about. And I am grateful I can experience them this way, in case, I don’t make it back to this beautiful land. I so appreciate your gifts. Visual as well as the story telling. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hello Bobbie,

Thank YOU so much for your generous message. I’m glad you enjoyed the armchair tour, but I hope you do get to return to Ireland one day. Thanks for taking a moment to write!

LikeLike